If I told an advertiser that 1 in 3 Canadians recalled some aspect of their advertising campaign, they would probably jump for joy.

But, according to a recent article in the Ottawa Citizen, spending $8-million dollars on a public health campaign that was recalled by “fewer than four in 10” of the people surveyed can be characterized as an “unnoticed”.

If we speculate that “fewer than 4 in 10” means a recall rate of between 35 and 39%, then we can begin to spin this article in the other direction. If 1 in 3 Canadians could recall any particular ad they’ve seen in the past week, I would deem that a success.

There needs to be change in expectations and techniques to evaluate these sorts of public service announcement campaigns, with modern media consumption factors and particular audiences in mind.

Factoring in advertising blindness

As we’re bombarded with hundred of advertisements each day, in varying media and with varying effectiveness, it’s becoming more difficult to directly inject thoughts into the minds of a population. In my college days, this was called the hypodermic needle model of communication – where every person was patiently waiting to absorb the message in its entirety.

Of course, audiences are far from patient and far from attentive, no matter the advertising medium in question.

Many media consumers – and, I might speculate, especially young people – have developed a form of advertising blindness to visual ads. In other media, people simply aren’t listening or comprehending the message that is being served. The message smacks us in the face and bounces right off – with nothing penetrating into the intended recipient’s active mind.

In the health awareness campaign in question, the message was sent out across many media with varying results.

“Just 21 per cent saw the magazine ads, 15 per cent noticed posters or digital signs in shopping malls, 12.6 per cent remembered Internet banner ads, six per cent recalled seeing cinema ads, and practically no one — just 3.2 per cent — spotted the campaign’s Facebook page,” the article said.

The survey occurred while the campaign was still running, but coming to an end, in early 2011. The article does not mention how many total respondents were surveyed.

Ask the intended audience

The Ottawa Citizen seemed to believe that the most important factor was whether this campaign reached any Canadians (and it did reach about 4 in 10). But, this should not be the measure of success for the campaign.

As the campaign was meant to “raise parental awareness of child health and safety issues”, then you might as well cut to the chase and simply survey parents – the intended audience. This is the only group that is likely to take any action after seeing the campaign anyway.

The article does scratch the surface of this issue by saying that “the campaign appears to have registered a bit more strongly with its target audience, parents with children 16 or younger. Among that group, 46 per cent had unaided recall of its advertisements, compared to just 34 per cent of non-parents.”

…So why are we surveying people who were not targeted by the campaign?

Apparently, the campaign had a lesser mental impact on the people it was irrelevant to. Does this finding surprise anyone? Would you expect a Jamaican tourist to recall an ad for snowmobiles they may or may not have seen as they walked through a Canadian airport?

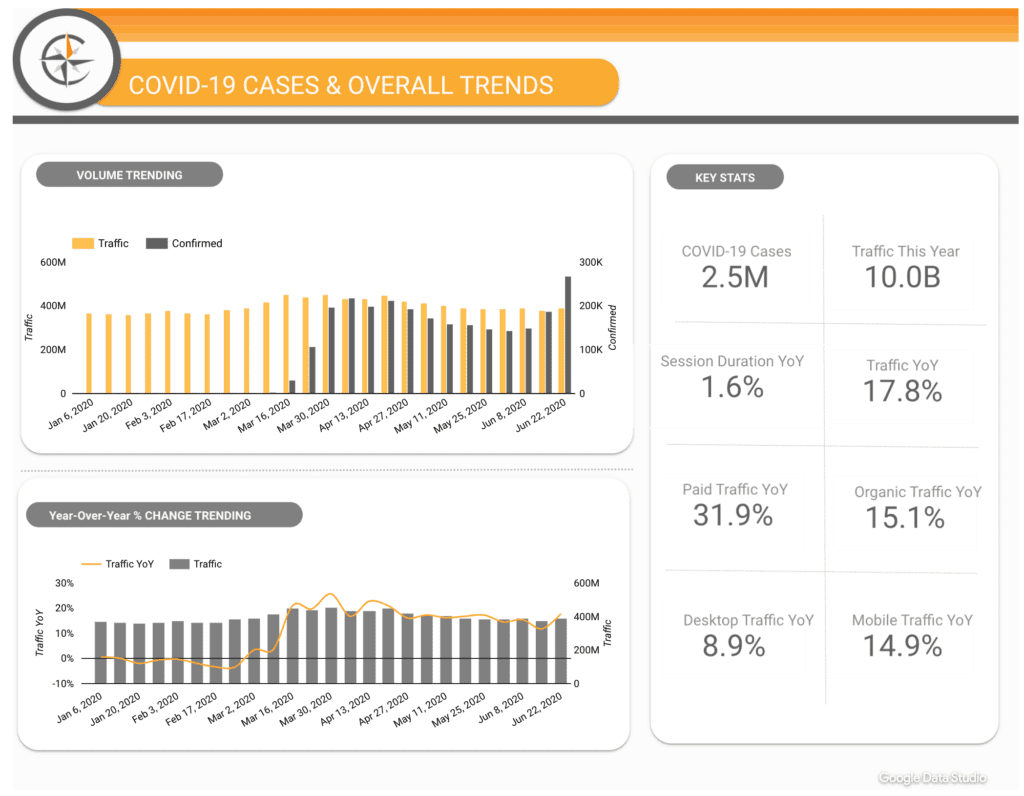

Get some modern measurement

In a modern media setting, measuring campaign success can go far beyond a general survey of Canadians. We have the technology to track visitors from advertising and back to the the website. We can measure interest in subjects like car-seat safety, bullying, and child immunization by Google search volume.

The article says that “barely more than seven per cent of those who took any action said they visited the site [created for the campaign – Healthycanadians.gc.ca/kids].” Maybe the campaign raised awareness, but some Canadians found their information through sources other than the site created for the campaign.

Ultimately, the surveyors did the campaign a disservice by surveying too broad an audience, and the Ottawa Citizen decided to take the easy ‘tax-payer outrage angle’ rather than consider the opposite spin. The experts consulted in the article didn’t seem to put much thought into evaluating the statistics presented to them either.

A better survey of the target audience, parents, and a more comprehensive sample of Canadian may have revealed a more complete picture of the campaign’s failures and successes.